Adding a system call to xv6

What are we doing??

We will add a system call to the XV6 kernel to understand how a user program can ask the kernel how to do a privilege operation. I will try to explain some basic concepts first and then show you the code. The source code for the XV6 kernel is here.

Background

What is a system call?

To understand why we need a system call, we need to know about limited direct execution (LDE). Imagine a world without laws, everything will wreak havoc, traffic will be a nightmare to participate in, and everyone will want everything for themself. It is the same for operating systems, user programs can use CPUs as long as they want without considering other programs. Without control, processes can take over the machine, accessing information that it is not allowed to access.

Limited direct execution is the idea that user program can execute their code directly on the CPU while being “limited”. Limited means that the OS makes sure the program doesn’t do anything that we don’t want it to do which is restricted operations. Also when the process is running, the OS can stop user programs and switch to another process so that resources on a machine can be shared. A system call is an interface that the OS provides us so that it can provide restricted operations.

A system call is the kernel's interface for a user program to access computer resources in a restricted manner. System calls like fork(), exec(), wait(), kill() allow programs to create new processes, execute different programs, synchronize with child processes, and terminate processes. There are also I/O operations such as open(), read(), write(), close(). In today's modern operating system, there are more than hundreds of system calls provided by the OS. With LDE, user programs are executed in user mode, when they want to access restricted resources such as (memory, I/O, etc), programs will use system calls to ask the kernel that runs in kernel mode to execute privilege operation on behalf of user programs.

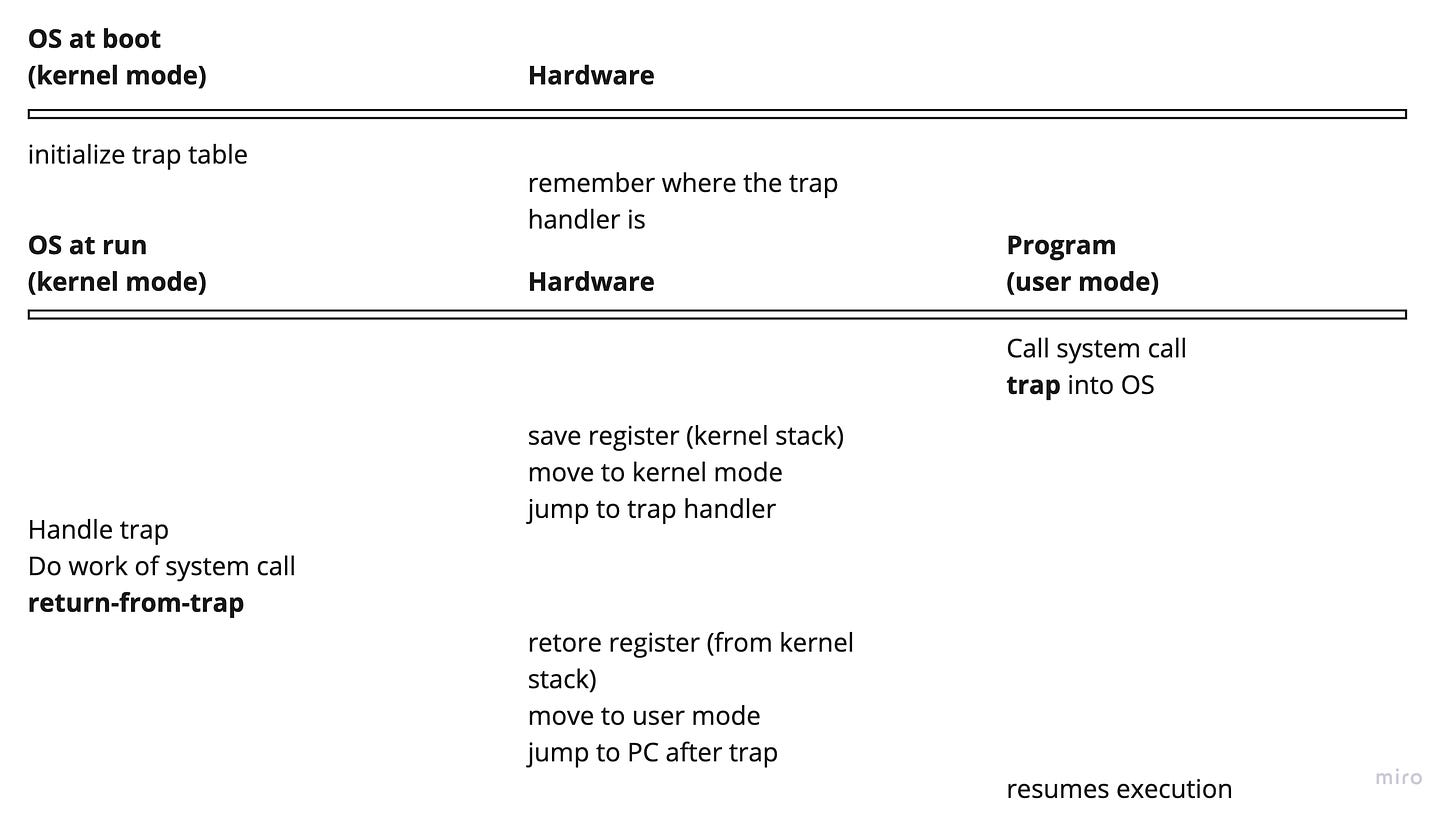

What happens during a system call?

When a user program makes a system call, it executes a special trap instruction. The instruction causes the processor to switch to the kernel (switch to kernel stack), raises the privilege level to kernel mode, and starts executing kernel instructions. Upon completion, the processor returns to user-space, the hardware lowers its privilege level, switches back to the user stack, and resumes executing user instructions.

The XV6 kernel code

System calls are one of three cases when control must be transferred from a user program to the kernel, the others are exceptions and interrupts. Lots of processors handle these events by a single hardware mechanism, in this case, the source code of xv6 is built on x86 architecture which uses the int instruction to invoke an interrupt. Use programs can invoke a system call by generating an interrupt using the int instruction. An interrupt stops the loop of a processor and starts executing an interrupt handler. The hardware raises the privilege level and saves the user program’s registers in its kernel stack so that it can resume executing after returning to user programs.

On the x86, interrupt handlers are defined in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT) which has 256 entries. A system call is defined as the 64th entry.

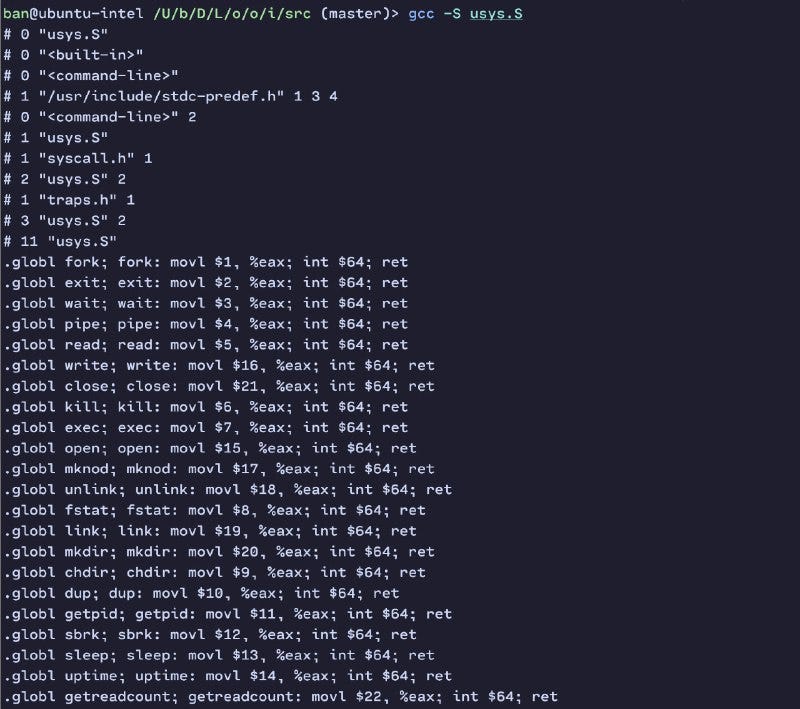

Let's look at how a user programs make a system call:

// FILE: usys.S

#include "syscall.h"

#include "traps.h"

#define SYSCALL(name) \

.globl name; \

name: \

movl $SYS_ ## name, %eax; \

int $T_SYSCALL; \

ret

SYSCALL(fork)

SYSCALL(exit)

SYSCALL(wait)

SYSCALL(pipe)

SYSCALL(read)

SYSCALL(write)

SYSCALL(close)

SYSCALL(kill)

SYSCALL(exec)

SYSCALL(open)

SYSCALL(mknod)

SYSCALL(unlink)

SYSCALL(fstat)

SYSCALL(link)

SYSCALL(mkdir)

SYSCALL(chdir)

SYSCALL(dup)

SYSCALL(getpid)

SYSCALL(sbrk)

SYSCALL(sleep)

SYSCALL(uptime)

Let’s compile this code to see what it does

As we can see for the fork() system calls, we will move the constant number 1 into the %eax register, then we will call the int instruction with 64 as the interrupt number for system calls, after executing the kernel will call ret which will handle the return-from-trap.

Setting up Trap Tables

At the OS is booting up, it is running in kernel mode, so that it can configure the machine hardware. OS must tell the hardware what code to run on certain events such as system calls, traps, or interrupts (this blog will focus only on system calls). The OS must inform the hardware where the trap handler is.

// FILE: main.c

int

main(void)

{

// ..

tvinit(); // trap vectors

// ..

}

In main.c, tvinit is where the trap table is set up.

// FILE: trap.c

void

tvinit(void)

{

int i;

for(i = 0; i < 256; i++)

SETGATE(idt[i], 0, SEG_KCODE<<3, vectors[i], 0);

SETGATE(idt[T_SYSCALL], 1, SEG_KCODE<<3, vectors[T_SYSCALL], DPL_USER);

initlock(&tickslock, "time");

}

// These are arbitrarily chosen, but with care not to overlap

// processor defined exceptions or interrupt vectors.

#define T_SYSCALL 64 // system call

SETGATE() macro is used to set the IDT array to the proper code to execute. What we want to look at is the SETGATE out of the loop. The value vectors[T_SYSCALL] is passed in, which means that it tells the hardware vectors[T_SYSCALL] is the trap handler for IDT[T_SYSCALL].

Let’s look at what is defined in vectors.S which can be compiled using Perl.

perl vectors.pl > vectors.S

# sample output:

.globl vector64

vector64:

pushl $64

jmp alltraps

Some interrupts have error codes, system calls will push 0 as a dummy error code. As mentioned above, system calls, exceptions, and interrupts are handled by one hardware mechanism, that is why we need a dummy error code for system calls. Next, it will push an interrupt number which again for system calls will be 64. Finally, it will jump to alltraps.

Current flow:

initialize the trap table

user program makes a system call ← We are here

put the number of the system call we want to call in

%eaxregisterinvoke

intwith the interrupt number

hardware saves the needed registers and jumps to the C trap handler

returns to the user program

Hardware Task to the C Trap handler

Before going to the C Trap handler, the hardware will do several tasks that are hard for software to do by itself. Saving the current program counter %eip on the kernel stack (%eip will point to the next code to be executed in the user program), then it will save other registers such as %eflags (current status of the CPU, etc., interrupt flags, privilege level,…, the stack pointer.). These registers will be saved on the trapframe of the process. We can see what the hardware will save for us by looking at the struct trapframe in the file x86.h

// FILE: x86.h

struct trapframe {

// registers as pushed by pusha

uint edi;

uint esi;

uint ebp;

uint oesp; // useless & ignored

uint ebx;

uint edx;

uint ecx;

uint eax;

// rest of trap frame

ushort es;

ushort padding1;

ushort ds;

ushort padding2;

uint trapno;

// below here defined by x86 hardware

uint err;

uint eip;

ushort cs;

ushort padding3;

uint eflags;

// below here only when crossing rings, such as from user to kernel

uint esp;

ushort ss;

ushort padding4;

};

After the interrupt handler is invoked, it will jump into alltraps.

#include "mmu.h"

# vectors.S sends all traps here.

.globl alltraps

alltraps:

# Build trap frame.

pushl %ds

pushl %es

pushl %fs

pushl %gs

pushal

# Set up data segments.

movw $(SEG_KDATA<<3), %ax

movw %ax, %ds

movw %ax, %es

# Call trap(tf), where tf=%esp

pushl %esp

call trap

addl $4, %esp

# Return falls through to trapret...

.globl trapret

trapret:

popal

popl %gs

popl %fs

popl %es

popl %ds

addl $0x8, %esp # trapno and errcode

iret

alltraps will first push segment registers onto the stack (while xv6 uses paging as a mechanism for memory management, the kernel still needs segments), pushall will push all general-purpose registers. Then it will set up data segment for kernel operations. pushl %esp pushes the current stack pointer onto the stack which is all the things that we have pushed so far. Then we will jump the trap() function in C. When trap() returns, we will ignore its return value by moving the stack pointer just above it (same as popping off the stack). The code execution will fall through to the trapret beloved which is the return-from-trap that will restore our registers, lower the privilege level, and return us to the user program.

Current flow:

initialize the trap table

user program makes a system call

put the number of the system call we want to call in

%eaxregisterinvoke

intwith the interrupt number

hardware saves the needed registers and jumps to the C trap handler ← we are here

returns to the user program

The C Trap handler

Let’s look at the trap() function:

void

trap(struct trapframe *tf)

{

if(tf->trapno == T_SYSCALL){

if(myproc()->killed)

exit();

myproc()->tf = tf;

syscall();

if(myproc()->killed)

exit();

return;

}

// ..

}

As we see in the alltraps, we pushed the stack pointer onto the stack which is the trapframe argument for this function. This code is called upon interrupts, exceptions, and system calls and thus it checks if the trapno is for system calls. It saves the current trapframe and then jumps to syscall().

Let’s look at the syscall function:

static int (*syscalls[])(void) = {

[SYS_fork] sys_fork,

[SYS_exit] sys_exit,

[SYS_wait] sys_wait,

[SYS_pipe] sys_pipe,

[SYS_read] sys_read,

[SYS_kill] sys_kill,

[SYS_exec] sys_exec,

[SYS_fstat] sys_fstat,

[SYS_chdir] sys_chdir,

[SYS_dup] sys_dup,

[SYS_getpid] sys_getpid,

[SYS_sbrk] sys_sbrk,

[SYS_sleep] sys_sleep,

[SYS_uptime] sys_uptime,

[SYS_open] sys_open,

[SYS_write] sys_write,

[SYS_mknod] sys_mknod,

[SYS_unlink] sys_unlink,

[SYS_link] sys_link,

[SYS_mkdir] sys_mkdir,

[SYS_close] sys_close,

};

void

syscall(void)

{

int num;

struct proc *curproc = myproc();

num = curproc->tf->eax;

if(num > 0 && num < NELEM(syscalls) && syscalls[num]) {

curproc->tf->eax = syscalls[num]();

} else {

cprintf("%d %s: unknown sys call %d\n",

curproc->pid, curproc->name, num);

curproc->tf->eax = -1;

}

}

Each system call has a number so that we know which will be revoked. Remember that we push a constant number before into the %eax register before calling the int instruction in usys.h. Now we retrieve that number from the trapframe so that we can call the corresponding system calls. The %eax register is also used for return values which is why we assign it back after we invoke the syscalls.

With this, we are done with all we need to know about how system calls are handled. Now we will add a system call of our own.

Adding a System Call

We will a system call getreadcount which will count how many times the read system call has been called.

First, let’s add our system calls logic in sysfile.c

// FILE: sysfile.c

int readcount = 0; // readcount will be incremented each time read() is called

struct spinlock readlock; // for thread-safe

// init the lock

void sysinit(void) {

initlock(&readlock, "read");

}

int

sys_getreadcount(void)

{

int count = 0;

acquire(&readlock);

count = readcount;

release(&readlock);

return count;

}

int

sys_read(void)

{

struct file *f;

int n;

char *p;

acquire(&readlock);

readcount++;

release(&readlock);

if(argfd(0, 0, &f) < 0 || argint(2, &n) < 0 || argptr(1, &p, n) < 0)

return -1;

return fileread(f, p, n);

}

Next, we will define our system call number for getreadcount()

// FILE: syscall.h

// System call numbers

#define SYS_fork 1

#define SYS_exit 2

#define SYS_wait 3

#define SYS_pipe 4

#define SYS_read 5

#define SYS_kill 6

#define SYS_exec 7

#define SYS_fstat 8

#define SYS_chdir 9

#define SYS_dup 10

#define SYS_getpid 11

#define SYS_sbrk 12

#define SYS_sleep 13

#define SYS_uptime 14

#define SYS_open 15

#define SYS_write 16

#define SYS_mknod 17

#define SYS_unlink 18

#define SYS_link 19

#define SYS_mkdir 20

#define SYS_close 21

// our system call

#define SYS_getreadcount 22

In syscall.c, we will define an extern function so that the compiler will make it global, as well as add it to the syscalls array.

extern int sys_chdir(void);

extern int sys_close(void);

extern int sys_dup(void);

extern int sys_exec(void);

extern int sys_exit(void);

extern int sys_fork(void);

extern int sys_fstat(void);

extern int sys_getpid(void);

extern int sys_kill(void);

extern int sys_link(void);

extern int sys_mkdir(void);

extern int sys_mknod(void);

extern int sys_open(void);

extern int sys_pipe(void);

extern int sys_read(void);

extern int sys_sbrk(void);

extern int sys_sleep(void);

extern int sys_unlink(void);

extern int sys_wait(void);

extern int sys_write(void);

extern int sys_uptime(void);

// OSTEP project

extern int sys_getreadcount(void);

static int (*syscalls[])(void) = {

[SYS_fork] sys_fork,

[SYS_exit] sys_exit,

[SYS_wait] sys_wait,

[SYS_pipe] sys_pipe,

[SYS_read] sys_read,

[SYS_kill] sys_kill,

[SYS_exec] sys_exec,

[SYS_fstat] sys_fstat,

[SYS_chdir] sys_chdir,

[SYS_dup] sys_dup,

[SYS_getpid] sys_getpid,

[SYS_sbrk] sys_sbrk,

[SYS_sleep] sys_sleep,

[SYS_uptime] sys_uptime,

[SYS_open] sys_open,

[SYS_write] sys_write,

[SYS_mknod] sys_mknod,

[SYS_unlink] sys_unlink,

[SYS_link] sys_link,

[SYS_mkdir] sys_mkdir,

[SYS_close] sys_close,

// OSTEP project

[SYS_getreadcount] sys_getreadcount,

};

With this, we are done with adding code in kernel code. We expose this function to the user. In user.h, we define getreadcount() so that users can call this function. We also add an entry in usys.S, this file will generate the stub for user programs to call or function.

// FILE user.h

// system calls

int fork(void);

int exit(void) __attribute__((noreturn));

int wait(void);

int pipe(int*);

int write(int, const void*, int);

int read(int, void*, int);

int close(int);

int kill(int);

int exec(char*, char**);

int open(const char*, int);

int mknod(const char*, short, short);

int unlink(const char*);

int fstat(int fd, struct stat*);

int link(const char*, const char*);

int mkdir(const char*);

int chdir(const char*);

int dup(int);

int getpid(void);

char* sbrk(int);

int sleep(int);

int uptime(void);

// OSTEP project

int getreadcount(void);

// FILE usys.S

#include "syscall.h"

#include "traps.h"

#define SYSCALL(name) \

.globl name; \

name: \

movl $SYS_ ## name, %eax; \

int $T_SYSCALL; \

ret

SYSCALL(fork)

SYSCALL(exit)

SYSCALL(wait)

SYSCALL(pipe)

SYSCALL(read)

SYSCALL(write)

SYSCALL(close)

SYSCALL(kill)

SYSCALL(exec)

SYSCALL(open)

SYSCALL(mknod)

SYSCALL(unlink)

SYSCALL(fstat)

SYSCALL(link)

SYSCALL(mkdir)

SYSCALL(chdir)

SYSCALL(dup)

SYSCALL(getpid)

SYSCALL(sbrk)

SYSCALL(sleep)

SYSCALL(uptime)

SYSCALL(getreadcount)

Now we can write a user program to test our system call. Define a C code file in the xv6 source code. You will need to update the Makefile so that this file will be compiled into xv6.

// FILE test_1.c

#include "types.h"

#include "stat.h"

#include "user.h"

int

main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int x1 = getreadcount();

int x2 = getreadcount();

char buf[100];

(void) read(4, buf, 1);

int x3 = getreadcount();

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

(void) read(4, buf, 1);

}

int x4 = getreadcount();

printf(1, "XV6_TEST_OUTPUT %d %d %d\n", x2-x1, x3-x2, x4-x3);

exit();

}

Update the UPROGS in our xv6 Makefile. Then run make qemu-nox. Type ls to see all files, you should see test_1. Run test_1 to see what it prints out.

UPROGS=\

_cat\

_echo\

_forktest\

_grep\

_init\

_kill\

_ln\

_ls\

_mkdir\

_rm\

_sh\

_stressfs\

_usertests\

_wc\

_zombie\

_test_1\

This concludes the first ever blog written by me. I hope I was able to deliver what I understand to you. If something is wrong, please leave a comment.